written by SatyrPhil Brucato

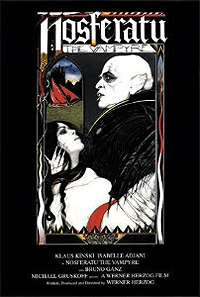

So, on Saturday night we watched the Werner Herzog‘s late-70s remake of the horror classic Nosferatu. As it stands, Herzog’s version is considered a classic in its own right. It’s taken me decades to get around to seeing it, but now that I have, I realize why that film enjoys its high reputation.

So, on Saturday night we watched the Werner Herzog‘s late-70s remake of the horror classic Nosferatu. As it stands, Herzog’s version is considered a classic in its own right. It’s taken me decades to get around to seeing it, but now that I have, I realize why that film enjoys its high reputation.

For starters, Nosferatu – The Vampyre displays Herzog’s signature blend of beauty and grotesquerie. Opening with images of real-life plague mummies entombed in European catacombs, the film recalls paintings by the Dutch Masters, sketches by Pieter Bruegel, and the art and music of the Romantic art movement. A landmark filmmaker fascinated by Nature’s implacable amorality (and humanity’s futile position within it), Herzog replaces the original Nosferatu’s Dracula-with-the-names-changed approach with Stoker’s original names, making it a more-or-less “official” adaptation of Stoker’s novel. In most respects, Herzog sticks more faithfully to the original text than most film adaptations do; his departures, however, feature Herzog’s own existential pessimism and a staggeringly downbeat ending. Through one intriguing choice, he forces his (in)famously robust and volatile leading man, Klaus Kinski, into a feeble shell of a performance – a statue-like apparition that recalls the mummies of the opening credits, combined with the plague rats that dominate the latter third of the film. Only twice does Kinski’s legendary physicality explode out of the stone-like Count Dracula… and the results are startling as you might expect.

Now, I could go on about the many levels of artistry in the film; ruminate on Herzog’s spellbinding nihilism; and contrast the vast differences between America’s innate (and often naive) optimism verses Germany’s Teutonic fatalism. What the film got me thinking about this morning, though, were the six core aspects of horror and the ways in which they work.

More often than not, we get wrapped up in the trappings attributed to “horror stories” – vampires, chainsaws, thunderstorms and so forth – and forget what makes horror HORROR. As I’ve noted in this journal before, artists and audiences keep confusing supernatural action thrillers with horror stories; thus, movies like Underworld get classified as “horror films” because they have vampires, while truly horrific movies like Closet Land get lumped under “drama” if they get noticed at all.

The key to horror as a genre is dread: a sense of fearful anticipation flavored with awe (*1). Generally, I think of “horror” (*2) stories as tales taking place in a hostile world filled with dread, featuring characters who may or may not be “heroic,” thrown against threats they may or may not survive. Ideally, a horror tale, regardless of medium, evokes that sense of vicarious dread and impending doom in its audience.

Like the faerie tales they resemble (and, in many senses, are), horror stories help us cope with the human condition by dressing up its challenges in larger-than-life style. As I wrote in Deliria: Faerie Tales for a New Millennium, faerie tales are not “escapes” from adulthood but methods of coping with adulthood (*3) . In horror tales, though, the primary challenge faced is not adulthood but mortality – the intimate inevitability of death. Without that element, a story can have vampires, chainsaws and thunderstorms, yet be utterly without “horror” in the truest sense. (*4) Both versions of Nosferatu definitely qualify as “horror” by those criteria; Herzog’s version, though, is a true distillation of mortal dread.

Like the faerie tales they resemble (and, in many senses, are), horror stories help us cope with the human condition by dressing up its challenges in larger-than-life style. As I wrote in Deliria: Faerie Tales for a New Millennium, faerie tales are not “escapes” from adulthood but methods of coping with adulthood (*3) . In horror tales, though, the primary challenge faced is not adulthood but mortality – the intimate inevitability of death. Without that element, a story can have vampires, chainsaws and thunderstorms, yet be utterly without “horror” in the truest sense. (*4) Both versions of Nosferatu definitely qualify as “horror” by those criteria; Herzog’s version, though, is a true distillation of mortal dread.

As a lifetime fan of horror films, stories and archetypes, I’ve noticed six approaches to horror that appear within such tales:

Body Horror – dread of physical fragility and corruption

Psychological Horror – dread of mental fragility and insanity

Elemental Horror – dread of the natural world and its non-human inhabitants

Spiritual Horror – dread of gods, spirits, restless souls, afterlives, and our relationship with them

Social Horror – dread of our fellow human beings and their institutions

Existential Horror – dread that we’re small and alone in an implacable cosmos

Naturally, you can mix-n-match those six aspects of dread within a single tale. Everyone has different thresholds of fear, and so a story like Dawn of the Dead (which employs all six aspects) carries a bigger punch than, say, Halloween (which nails Body, Social, perhaps Psychological and – if you push it – Existential Horror) or the Friday the 13th series (which doesn’t make it past Body and maybe Social Horror).

Each aspect has variations, too – elements within that group that play on certain related fears. Body Horror, for example, can be carved up (so to speak) into Sex, Disease, Mutilation, Deformation, Excretion, Freakishness, Transformation, Decrepitude, Decay, Crippling, and flat-out Gore. A true “master of terror” like Stephen King can play those aspects and their variations like an evil pipe organ – pulling stops, pushing pedals and striking chords all over the spectrum. Since different people have different “buttons” regarding dread, a well-rounded storyteller can employ the six aspects of horror and explore the many variations within those aspects as well.

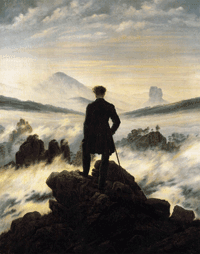

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich. Echoed in Herzog’s Nosferatu, this painting captures the terrible beauty of untamed Nature – a primary source of Elemental Horror within Romantic art and Herzog’s film.

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich. Echoed in Herzog’s Nosferatu, this painting captures the terrible beauty of untamed Nature – a primary source of Elemental Horror within Romantic art and Herzog’s film.

Horror, as King often says, is the basement level of our daily lives. Down there, hungry alligators wait to devour us. Some folks have ravenous gators, quite a few have playful ones, many have ones that pop up unexpectedly, and large numbers deny that the gators are even there until those beasts eat their way up through the floorboards and devour our guests. (Many folks often deny them even then.) No one, however, is immune. Legacies of the human condition, those gators are always there somewhere.

As Werner Herzog understands, the human condition is ripe with terrors. Your fears might not be my fears, but none of us are without fear of any sort. His Nosferatu – awful in its beauty and redolent with putrefaction – got me thinking about fear, its appeal, and its applications within the stories we create and enjoy. Whether or not we enjoy confronting those fears through horror books or movies, the urge to look into the basement still haunts us. As Keef told Meghan in Arpeggio, no matter who we think we might be, fear finds us all.

——————–

Tremble Before the Inevitable Footnotes!

——————–

- *1 – The word’s root comes from the Old English term ondraedan – “to advise against.”

*2 – Some purists prefer the term “terror” over “horror.” Technically, horror refers to the physical sensation of fearful revulsion, while terror denotes a fearful state of mind. Regardless, “horror has a better ring to it, and has decades of tradition behind this usage.

*3 – Deliria, pages 146-152. By the way, I have copies of this out-of-print book for sale.

*4 – The same is true of comedy, in which catastrophe is played for laughs. As I say in my storytelling classes, the difference between comedy and tragedy involves scope, pacing, consequences and connection: “Scope” is the size of the catastrophe, “pacing” is the speed of its events, “consequences” are the long-term results of that disaster, and “connection” measures how closely you can relate to it. Comedy, for the most part, is tragedy exaggerated to the point of absurdity. Replace “tragedy” with “horror” and you see why movies like Shawn of the Dead work so well.

Essay copyright(c) SatyrPhil Brucato 2010. Permission granted for reposting with attribution. Reprinting for profit without attribution or permission is prohibited.